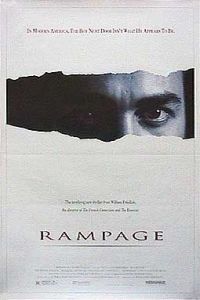

Rampage (1987), directed by William Friedkin

Thriller and courtroom drama about a whackjob who savagely kills five people and the prosecutor who, theoretically conflicted, argues in favor of the death penalty. Based on the book by William P. Wood and “inspired by” true events — the case of serial killer Richard Chase. Friedkin (who produced, wrote, and directed the film) provides no easy answers, yet fails to provide much in the way of food for thought, either, despite tackling both the death penalty and legal insanity. Alex McArthur handles the “innocence” of insanity quite well (he’s certainly a cheerful maniac) and Michael Biehn is good as the prosecutor; the script, however, never allows either of them to dig very deeply into their characters or the issues surrounding them. Which is just as well, as the ending undercuts their differing psychologies anyway. Originally released in Europe with a different ending; re-cut and modified for US release by Friedkin after studio bankruptcy left the movie stranded on the shelf for five years. Less violent than you might expect: the really horrible stuff occurs off-screen.

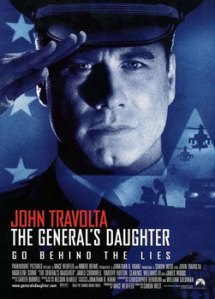

The General’s Daughter (1999), directed by Simon West

So I’m watching The General’s Daughter, it’s nearly over, and I already know what I’m going to say about it. Then something magical happens: screenwriters Christopher Bertolini and William Goldman say it for me. Bad adaptations are typically bad for a number of reasons. This one is different. Everything that is wrong with this movie is encapsulated in a single mistake in judgment. And Bertolini and Goldman, almost as if they were proud of it, spell it out and practically sign it, right there in the screenplay.

It’s so brazen, I feel as though I should reward them for it. So I’ll let them tell you what they did to turn an excellent novel into a poor movie.

In the book, at the very end, narrator Paul Brenner muses, “The human eye can distinguish 15 or 16 shades of gray. A computer image processor can distinguish 256 shades of gray, which is impressive. More impressive, however, is the human heart, mind, and soul, which can distinguish an infinite amount of emotional, psychological, and moral shadings, from the blackest of black to the whitest of white. I’ve never seen either end of the spectrum, but I’ve seen a lot in between.”

In the movie, again near the end, Paul watches murder victim Captain Campbell, who works in Psychological Operations, or Psy-Ops, speaking about her job on a videotape. She says, “The human eye can distinguish 16 shades of gray. A computer image processor, analyzing a fingerprint, can distinguish 256 shades of gray, which is impressive. The human heart, mind, and soul, however, can distinguish an infinite number of emotional, psychological, and moral shadings. In Psy-Ops, we deal with the blackest of black and the whitest of white.”

Brenner is talking about the real world. Campbell is talking about Hollywood.

Captain Campbell (here named Elisabeth instead of Ann for some reason) is found murdered — naked, spreadeagled, and staked to the ground. Paul Brenner of the Army’s Criminal Investigations Division must find out what happened to her. The basic story, then, remains intact. But this is itself a mistake, for this crime is too horrible to be reduced to black and white. Where the novel was about bringing Campbell to life and confronting us with the moral, ethical, and psychological contradictions of her existence and eventual death, the movie is about nothing more than identifying and punishing the bad guys (one of whom, gratuitously, is turned into a homosexual).

Having made the decision to sweep any shading under the rug, the filmmakers knew they had to replace it with something. I’m guessing it took them about two seconds to settle on their answer: action and mortal danger. In this kind of movie, bullets and shrapnel are what pass for penetrating stuff.

A bad adaptation doesn’t necessarily entail a bad movie. I knew where this one was going in the first 15 minutes or so, but it was enjoyable, and I was prepared to like it. I’ve liked John Travolta since his Sweathog days, and I was pleased to see his flagging career revived with Pulp Fiction. I wanted to like this movie. But polarization means simplification, which, sometimes, morphs into trivialization. And that’s what happened here. Captain Campbell’s character deserved more than justice; she deserved respect.

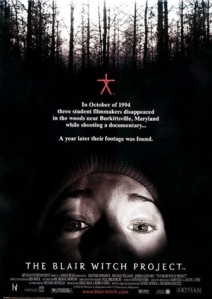

The Blair Witch Project (1999), directed by Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick

I don’t really have much to say about this movie. Many critics raved about it, and it’s certainly popular, but it isn’t very good. The best thing about it, really, was its marketing, specifically the website created for it, which treated the whole thing, as did the movie itself, as if it really happened. It was a brilliant idea, but the brilliance stopped there.

I deplore the “found footage” thing — not on principal but because what I’ve seen of it is crap — but I don’t hold that against Blair Witch, which was the source of the modern wave. At the time, it was novel and vaguely interesting because of it. That’s when I first saw it, not long after it was released. And at the time I thought, Well, it’s all right, but nothing to write home about. Having recently seen it again, I came to the same conclusion.

I’m sure you know this already, but it’s about three kids who go into the woods to make a documentary about a local legend, “the Blair Witch.” They get lost, find strange figures made of sticks, hear noises, and become increasingly unglued. Ostensibly it’s all very scary.

Occasionally, it even is. But most of the time, it’s herky-jerky photography, dull dialogue, and decision-making that would make a typical slasher victim proud. Cause, you know, it isn’t real. It’s a movie. And it needed better planning and a much better script. Had it had those things, it might be fair to look at the later movies in the same genre and say they just don’t get it. Instead, they do get it: grab a camera and wing it. But the novelty’s worn off.

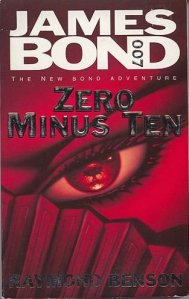

Zero Minus Ten (1997) by Raymond Benson

Benson’s first James Bond book begins in the worst way imaginable, with a training exercise we’re supposed to believe is a real operation, then settles into a story of nuclear threat and corporate intrigue set against the 1997 British handover of Hong Kong to the Chinese, finally returning to silliness in the climax. The bad guy pokes fun at villains who devise special means of killing their enemies, then proceeds to do the same thing. Readers who found Ian Fleming’s descriptions of Bond’s gambling (at cards, at golf) too long and detailed will be buried by Benson’s homage, as he plays out a game of mahjong over two chapters and 20 pages.

Both Bond and the book, however, hew closer to Fleming’s than did John Gardner’s, though noticeable and regrettable deviations remain. One of these has to with M (this is the new, female M). Benson goes to some length to position her as a real no-nonsense type, then efficiently undermines her authority by having her recognize Bond as a “loose cannon,” one who can seemingly ignore her direct orders with impugnity. Unlike Gardner, Benson recognizes Bond’s chivalrous attitude toward women, but doesn’t adopt it, his Bond having abandoned all hope of lasting love.

As a spy novel, Zero sounds about right — the plot works like Bond’s “spy kit,” which, though scaled down to fit in the heels of his shoes, contains everything he needs in a pinch — yet as a Bond novel, it is reasonably entertaining. The hope can only be that the series will improve, though as the author’s qualifications for the job include designing software “products” and his tenure as Vice President of the American James Bond 007 Fan Club, this is faint hope indeed.

The Disembodied (1957), directed by Walter Grauman

Decent low-budget affair set in the African jungle. Sultry Allison Hayes plays Tonda, a “voodoo queen” who would rather have the young and handsome leader of a passing expedition than her much older doctor husband. The voodoo rites aren’t as compelling as those in I Walked With a Zombie, but, like the entire film, they aren’t that bad, either. One poor native woman loses her husband twice. Definitely worth a look for fans of classic, low-budget horror.

Carrie x 4

“I’ve heard rumblings about a Carrie remake….Who knows if it will happen? The real question is why, when the original was so good? I mean, not Casablanca, or anything, but a really good horror-suspense film, much better than the book.” – Stephen King, as quoted in Entertainment Weekly, May 2011

“I’ve heard rumblings about a Carrie remake….Who knows if it will happen? The real question is why, when the original was so good? I mean, not Casablanca, or anything, but a really good horror-suspense film, much better than the book.” – Stephen King, as quoted in Entertainment Weekly, May 2011

Of course, King knows why, and the 2013 remake, directed by Kimberly Peirce, didn’t disappoint: after recouping its $30M budget, it went on to make an additional $50M worldwide. But he was right to question the remake’s necessity. Brian De Palma’s 1976 original is one of the best horror films ever made. And since, as King points out, it already tops the book, what remained to be done?

In fact, the book is an effective pot-boiler, but nothing more. In this sense, it was a perfect candidate for adaptation. That is, by someone who understands the implications of adapting a book like this. Brian De Palma did. But the producers of the remake, who evidently let it be known that the new script would be “more faithful” to the novel, clearly did not. It isn’t the kind of novel one should be “faithful” to; it is the kind of novel one should use as a springboard to something better.

And what is “more faithful” anyway? The new film begins with Carrie’s birth. Just as in the book, Carrie’s mom, Margaret, gives birth all by herself: she doesn’t hold with modern medicine and she certainly has no friends. On top of that, I think she’s still hoping the baby will turn out to be some weird tumor she can toss in the garbage along with the sin that produced it. But, no, it’s a baby, all right, and though she tries to kill it, she can’t bring herself to do it.

Now, in the book, the police find her hours later, exhausted, and with little Carrie at her breast. It was a battle, one that Margaret lost. In the movie, she goes soft on the little thing and cuddles her. It is the beginning of a strange new element in the story: Margaret’s “love” for Carrie. I suppose the Lord of Faithful Adaptations giveth with one hand, only to taketh away with the other.

Now, in the book, the police find her hours later, exhausted, and with little Carrie at her breast. It was a battle, one that Margaret lost. In the movie, she goes soft on the little thing and cuddles her. It is the beginning of a strange new element in the story: Margaret’s “love” for Carrie. I suppose the Lord of Faithful Adaptations giveth with one hand, only to taketh away with the other.

It does, however, tell you what you need to know about the remake’s definition of “faithful”: if a scene in the book is violent, it will try to include it.

To its detriment, it reproduces the vengeful side of Carrie’s personality. One of the reasons the original works so well is that De Palma (and screenwriter Lawrence D. Cohen) tossed most of that aside and focused on the girl, not the avenging angel. I enjoy watching Clint Eastwood wipe out the bad guys in all those “man with no name” movies, but that’s because the bad guys are evil and they are adults. As King has one of Carrie’s classmates point out in the book, we aren’t dealing with adults here, we’re dealing with kids. (She repeats this several times.) One or two of these kids might be evil, but the rest are just…kids. What this means is that, while we might sympathize with what Carrie thinks she would like to do to them, we can’t sympathize with her actually doing it. (I saw a question in a Goodreads group about Carrie: “did you cheer her on?” Good Lord, I hope not. She kills scores of kids, the great crime of most of whom was probably nothing more than that they ignored her.) It’s a subtlety that is lost on Peirce; consequently, we never feel for Carrie the way we did in the original film.

It isn’t for lack of trying on the part of the actors. While I certainly wouldn’t put Chloë Grace Moretz in Sissy Spacek’s league, she does well in the title role, and some of her scenes with Ansel Elgort, as Tommy Ross, the boy who takes Carrie to the prom, are quite sweet. But this is another thing De Palma had going for him: a killer cast: Piper Laurie (who, King said, “really got her teeth into the bad-mom thing”), William Katt (the embodiment of the All-American boy), Amy Irving, Nancy Allen (much more believable than Portia Doubleday as the girl who can “take her pick” of prom dates), and John Travolta (who does something extraordinary, playing both parts of his bad boy role, coming across as bad, yes, but also as a boy).

It isn’t for lack of trying on the part of the actors. While I certainly wouldn’t put Chloë Grace Moretz in Sissy Spacek’s league, she does well in the title role, and some of her scenes with Ansel Elgort, as Tommy Ross, the boy who takes Carrie to the prom, are quite sweet. But this is another thing De Palma had going for him: a killer cast: Piper Laurie (who, King said, “really got her teeth into the bad-mom thing”), William Katt (the embodiment of the All-American boy), Amy Irving, Nancy Allen (much more believable than Portia Doubleday as the girl who can “take her pick” of prom dates), and John Travolta (who does something extraordinary, playing both parts of his bad boy role, coming across as bad, yes, but also as a boy).

In 2002, television got into the act with its own Carrie adaptation. This one stars Angela Bettis as Carrie. (You might remember her as another eponymous character, from another film released the same year — May.)

The oddest thing about this adaptation, which in other respects is probably as good as the 2013 remake, is the ending: Carrie doesn’t die. Why? Because the film was originally intended as a pilot for a TV series. I don’t consider this a spoiler, because it’s really nothing more than a tacked-on ending setting up a series that, thankfully, never happened. According to the Stephen King Wiki, it was supposed to be about how Carrie moves to Florida to “help others with telekinetic problems.”

The reason to watch this one, if you like King’s book, is that it is the only adaptation to try to recreate the novel’s documentary approach. It begins with Sue Snell — the girl who convinces her boyfriend, Tommy, to take Carrie to the prom — being interrogated by the police. This is a couple of weeks after the disaster. Other interrogations follow periodically throughout the movie.

The reason to watch this one, if you like King’s book, is that it is the only adaptation to try to recreate the novel’s documentary approach. It begins with Sue Snell — the girl who convinces her boyfriend, Tommy, to take Carrie to the prom — being interrogated by the police. This is a couple of weeks after the disaster. Other interrogations follow periodically throughout the movie.

The other reason to see it is that it is also the only adaptation to depict the devastation that Carrie wreaks upon the town at the end. The other movies show what she does to the school and a gas station, but as any reader of the book knows, Carrie didn’t stop there. Neither does this movie.

These two elements more or less cancel out a bizarre twist at the end that was also probably dictated by the proposed series, but which I won’t reveal, other than to say that it manages to walk Carrie’s character right down the middle of the road, between “innocent” schoolgirl and vengeful spirit.

Book: ♦♦♦

1976 Film: ♦♦♦♦♦

2002 Telefilm: ♦♦½

2013 Film: ♦♦½

While I agree with Stephen King, I think that it can be said that De Palma’s Carrie is definitely one of the Casablancas of horror film.

King Kong (1976), directed by John Guillermin

Though both films follow the same narrative arc, the spirit of John Guillermin’s King Kong really starts where the original left off, with commercialism and corporate greed taking the place of adventure and heroism. Carl Denham, the brave but reckless moviemaker after the greatest animal picture of all time, is replaced by Fred Wilson (Charles Grodin), an oil company executive seeking to stick it to Shell and Exxon with the biggest oil strike ever. And perhaps this could have worked, if Wilson was half the hero that Denham was. But instead Jack Driscoll, Denham’s loyal first mate who “goes soft” on Ann Darrow, is himself replaced by Jack Prescott (Jeff Bridges), an outsider who stows away aboard the ship, and whose function (he’s a primate paleontologist and nature lover) is to show how evil Wilson is, while it’s unlikely he ever cares more about Dwan (Jessica Lange) than Kong. Not that Dwan’s any different: she’s young and naive, but also opportunistic and ambitious. This is a movie every bit as cynical as its poster, which proclaims in bold red letters that it is “the most exciting original motion picture event of all time” (emphasis mine).

I don’t want to give the impression that cynicism has no place in the movies, or even in this movie. It’s weak, toothless cynicism that bothers me. The mistake made here was Jack, specifically making Jack with his noble ideas the hero of the story. He weakens Wilson, who is, after all, the prime mover in all that happens, and he is, in the end, notably ineffectual. He’s a drag on the whole story. And this is the guy we’re supposed to identify with.

Him, or Kong. Kong’s a bunch of props and a guy in an ape suit, but he’s the most human character in the movie. The effects are uneven, but when they work, they’re quite effective, such as when we first see him plowing through the jungle on his way to take Dwan from her matrimonial altar and when, back in his lair, he plays with her and dips her under a waterfall.

But even Kong is weak here. The only other monster he (or anyone) fights is a sadly ridiculous snake and his rampage through the native village is stopped at its very gate. This isn’t Beauty and the Beast, it’s Beauty and the Misunderstood Loner. He’s too human. Making him a giant ape is merely an exercise in excess.

I do like segments of the film and the performances are good. Jessica Lange was criticized for her performance, but she also got handed the movie’s worst dialogue, so she was handicapped to begin with. But it is its own worst enemy, sapping its strength by going in too many directions at once. It does this, ironically, for the same reason Denham, in the original, brought a girl along in the first place — to please the masses. But, according to Denham, everyone wanted to see a pretty girl. Here, Guillermin and screenwriter Lorenzo Semple Jr., aren’t trying to unite the audience, they’re trying to please each part of it in their own way.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014), directed by Matt Reeves

Set 10 years after the events of Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Dawn opens with men and apes coexisting by staying out of each other’s way. But with his fuel stockpile running out and in desperate need of power for his city, human Malcolm (Jason Clarke) leads a small team into ape Caesar’s (Andy Serkis) forest home to ask permission to repair a hydroelectric dam. Nuts in each camp — led by Koba (Toby Kebbell) in the ape enclave and Dreyfus (Gary Oldman) in Zone 2, the human city — would rather wipe out the other side and be done with it. Frankly amazing ape effects that are so real they rarely amaze lay bare an all-too-conventional story of enemies learning to respect and care for each other. A movie with no surprises and little to delight the audience (other than a cute scene with a baby ape). And, in spite of the bad guys of both species understanding “human” nature better than their peace-loving leaders, no irony or satire either. Less a science fiction film than a slow-starting action movie, but well made.

Ender’s Game (1985) by Orson Scott Card

Ender’s Game is like a Kidz Bop version of “Bolero” — set on Repeat. It’s catchy, but awfully shallow, and its main idea is endlessly reiterated. Ender Wiggin, a brilliant young boy being groomed as a military commander, solves one new problem after another as he tackles a series of games and mock battles designed to teach him tactics, strategy, and command. Losing is not an option; neither is any limit to Ender’s ability. So each “test” is a fait accompli, and it’s just a matter of how many of them Orson Scott Card can cram into 300 pages.

Ender isn’t just brilliant, he’s the most brilliant human ever. This is reasonable because he’s also superhuman. Card says he first came up with the idea for Ender’s story when he was 16. That makes sense: Ender’s Game is an aggressive schoolboy fantasy. Ender is lonely, misunderstood, yet clearly better than everyone else. At everything.

This more than anything else, I think, explains the book’s popularity: it’s escape fiction extraordinaire. Ender’s not a deep boy so he’s easy to identify with, and the fact that the basic scenario replays itself so many times simply mirrors our daydreams. It’s a formula that defies monotony to a remarkable extent. I mean, there’s always more ass to kick.

Still, it’s hard to think of this book as anything more than a guilty pleasure. Ender is just too good, too smart, too tough. Even when the odds are so stacked against him that all he can do is something crazy, it turns out to be just the thing required. He absolutely cannot lose.

In sports, you hear all the time how if the play that just failed had worked, so-and-so would have been a genius, when the truth is that sometimes bad decisions turn out well and good decisions go to hell. For Ender, though, every decision is right, even those made in exhaustion after days of serious sleep deprivation. It’s easy enough to see why others would follow him — the real weirdos are the ones who don’t — but more difficult to see why I, as a reader, should care one way or the other.

Winner of both the Hugo and Nebula awards for Best Novel.

Devil’s Knot (2013), directed by Atom Egoyan

Unfocused dramatization of the events surrounding the 1993 murders of three 8-year-old boys in West Memphis, Arkansas, including the investigation, arrest, trials, and convictions of three teenage boys for the crimes. The teenagers, later known as the West Memphis Three, received additional notoriety when questions began to be raised about the case, with many believing that they are innocent. Based on a book of the same name by Mara Leveritt, who believes the teenagers were

targeted in a “witch hunt” similar to that which occurred in Salem, Massachusetts, in the late 1600s. The murders of the boys were linked by police and prosecutors to Satanism and Satanic ritual. Meanwhile, other leads, particularly one involving a black man who on the night of the murders reportedly entered a restaurant bleeding and disoriented, were ignored. That’s a lot of ground to cover for any dramatization, and there’s more besides, such as a woman and her son, both of whom appear to have lied to police: the woman about attending a satanic ritual with two of the accused, her son about having witnessed the murders.

More like a series of reenactments than a dramatization, the film fails to probe any aspect of the case or the people involved with any depth. That said, it opens well with Reese Witherspoon and young Jet Jurgensmeyer as mother and son, and the fateful if perfectly natural decision to allow the boy to go out riding bikes with his friends. The sequence ends with the discovery of the bodies. The bulk of the film, if viewed as a kind of primer on the case, is compelling enough, but those familiar with what happened may become bored by the wide-ranging superficiality of it all. Devil’s Knot is a deeply flawed film, but one which, for its subject matter and themes, may appeal to those interested in true crime.

Recent Comments