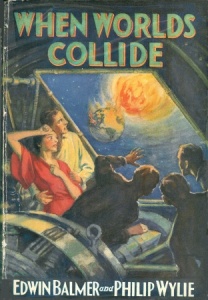

When Worlds Collide (1933) by Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer

All those other apocalyptic books with their puny viruses and piddling nuclear wars have nothing on When Worlds Collide, which is about the smashing of Earth itself into jagged little pieces.

Or it would be — if physics respected the three-act structure.

The book begins with the man who is carrying the fate of Mankind in his briefcase: photographic plates of two large planetary objects — one about the size of Neptune, one Earth-sized — that are on a collision course with the third planet in our little solar system. Yeah, that’s us. And ain’t nothin in the world can stop them. So what is going to happen to our planet is, to coin a phrase, written in the stars from page one. Well, at least there’ll be no more ads for Viagra.

The story — the one with some reasonable margin for error — is about the men and women who refuse to accept this fate. It turns out, you see, that the smaller body is not only about the same size as Earth, but also very Earth-like. If their calculations are correct, it will survive the collision of the other two planets and take up an orbit of its own about the Sun. So it’s just a matter of building a ship that can make the crossing. There’s just one catch: the ship envisioned can only house about a hundred people.

According to the blurb on the back of my mid-seventies paperback, this caveat “touch[s] off a savage struggle among the world’s most powerful men for the million-to-one chance of survival.” You’d think that it would, wouldn’t you? But, if you were anything other than a blurb writer, you’d probably want to read the book first before announcing it to the world. The fact is, no such thing ever happens.

In fact, this is one of the curious things about this novel. I could also have said “quaint.” “Charming” is another matter. It has that old-timey faith in science and scientists as the saviors of our world. It comes by this honestly — it was published in 1933 — but it makes, at times, for some…interesting…developments. For instance, government plays no role in the building of the spaceship. It is conceived by Dr. Cole Hendron (whose honorific is of the Ph, not the M, variety), and he alone gathers about him the people he believes he needs to succeed. He alone will decide who goes and who stays. Meanwhile, the President of the United States rallies the populace to die another day.

That most of “us” have several opportunities to die is determined by the fact that the invading planets make two passes of the Earth, not just one. The first is a near miss. But even a near miss, with the combined mass of Neptune and Earth, is catastrophic. Tidal waves, earthquakes, floods, volcanic activity — the world is torn apart. Well, all but torn apart; the actual rending comes later. In between, reduced in large part to barbarism, the remaining population finds more traditional ways to kill each other.

This is great stuff.

Keeping the home fires burning are Tony Drake and the chief’s daughter, Eve. But theirs is a romance with serious complications. If only a hundred people can survive, how can they justify monogamy? Tony, a simpler soul than Eve, thinks he can justify it just fine; Eve is more realistic. Enter David Ransdell, a real man’s man, whose appreciation of Eve’s charms is not altogether unrequited.

Flipping my paperback over, we find on the front cover the bold statement: “America’s most famous science fiction classic that ranks with 1984 and Brave New World.” Except that this book is largely forgotten and the other two are still considered classics. This, I’m here to tell you, isn’t quite fair. Literarily, no, When Worlds Collide isn’t in the same league. In terms of its vision, though, and its remarkable evocation of utter disaster, it actually is. This is a book in which shit not only happens, it obliterates practically everything.

I’m going to see the 1951 movie later today, but I can already tell you, if ever there was a story ripe for a remake, this is it. And it could be glorious.

King Kong (1933), directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack

“At a Hollywood party in 1972, I saw Hugh Hefner introduced to Fay Wray. ‘I loved your movie,’ he told her. ‘Which one?’ she asked.” – Roger Ebert

Fay Wray — not just the original scream queen.

If it wasn’t a classic, King Kong would be a hard sell to modern audiences. It’s dated in so many ways: in its acting, its special effects, its social values. Why bother, particularly now that we have Jurassic Park? I think the answer to that question is one major reason why King Kong is considered a classic and why it keeps charting on all those “best of” lists, including the granddaddy of them all, Sight & Sound‘s “Best Films” list, where, at 171, it ties with such movies as Star Wars, Notorious, and Goodfellas.

The answer is that grandeur never goes out of style. In its technical aspects and its imagination, King Kong remains an awesome achievement.

Even today, it stands apart from most other monster movies in its scale and scope. Despite the singularity of its title — there’s only one Kong — unlike other movies of its kind it doesn’t stop there. It doesn’t have one monster, it has eight. (Originally it had even more, but the scenes got cut.) It isn’t set on an island or plateau forgotten by time; Skull Island is inhabited — by primitives, it’s true — but primitives who maintain the great work of their ancestors, the giant wall separating them from Kong and the island’s other fantastic creatures. When Kong escapes in New York his destruction isn’t limited to one locale, he wreaks havoc over several blocks.

It’s violence is equally majestic. Re-released several times, censors cut out a good deal of it. They cut out people being bitten or trampled by Kong and they cut out the giant ape, perched high on the wall of a tall building, tossing a woman aside so that she plummets to her death on the street below. But all that has been restored. King Kong has what all monster movies ought to have — teeth. Kong is a beast, after all, and what cornered beasts do is kill if they can. Kong can.

The film has poetry, too. One high-angle shot of Ann Darrow, tied on the altar, with chanting natives at the top of the wall on one side and unknown horror on the other is almost cosmic. Another, of Kong undressing Ann and sniffing his fingers (oh, yes, the censors whacked that scene, as well) is funny but somehow beautiful at the same time. For Kong isn’t merely a monster. He is also a tragic hero. Fay Wray says she was promised the lead opposite the “tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood,” whom she assumed was Clark Gable. And in a way, it was.

One thing about the effects. They’re dated, sure, but they’re very good, and it’s obvious just how much care went into creating them. When Kong kills a T-Rex by breaking its jaw, blood flows out of its mouth. A little later, when the human hero finds the carcass, he frightens a scavenging Teratornis. The effects bring the island to life. The story is simple enough and so are the characters. But King Kong isn’t a superficial film. It makes up for what it lacks with remarkable imaginative depth.

She Done Him Wrong (1933), directed by Lowell Sherman

Listen, when women go wrong, men go right after them.

This movie simply doesn’t age. When I first saw it, as a college student, it was already 50 years old. Now it’s another 30 on top of that, and it’s just as bawdy, just as delightful as ever.

The main attraction, of course, is Mae West, whose overt sexuality would be comical if she didn’t back it up. But back it up she does. As Lady Lou, a singer in a Gay Nineties saloon and dance hall, West is intelligent, witty, poised, and possessed of enough self-confidence to power ten self-esteem symposiums. She’s the ultimate bad girl, and it’s no wonder every man who meets her is desperate to have her.

A very young Cary Grant plays Captain Cummings, who runs the church mission next door. He wants to save Lou’s soul; she wants to corrupt his. Meanwhile, a girl tries to commit suicide, a counterfeiting ring kicks into operation, a criminal escapes, and a woman is stabbed to death. All in just 66 minutes.

It’s tempting to call the plot a throwaway, nothing more than a vehicle for West’s double entendres and one-liners. That, however, would be like dissing the straight man in a comedy routine. The movie works as well as it does because the two are so perfectly matched. You’d think, given all that happens, that the movie is fast-paced, but it isn’t really until the very end. On the other hand, it doesn’t need to be: West is racy enough on her own.

She Done Him Wrong is the shortest movie ever to be nominated for Best Picture. It was right up there with Little Women, the good one, starring Katharine Hepburn. But that’s the way of it, isn’t it? Sentimentality is fine, but sometimes you just need to laugh.

Recent Comments